2000 Anaylsis of the Philadelphia Stadium

Situation

By Sandor Gulyas

I originally wrote this paper in 2000, hense the

title. In the time since I wrote this, I have have found more

support material concerning the history of the football and baseball

teams of Philadelphia in reference to their playing locations

within Philadelphia. That means somewhere down the line I will

be updating/rewriting this paper to reflect the knowledge I've

gain since I first wrote this. Stay Tuned....

There are a myriad decisions to be made before any city infrastructure

is built. From the county, city, or state lining up the political

support, arraigning

land assembly, tax rebates, and finances to the team deciding

on where (both macro and micro scale), scale of stadium, and their

investment into the process.

One of the current locations in the national stadium debate is

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. For six years now the city and, primarily,

their local baseball team, the Philadelphia Phillies, have been

debating about securing a new stadium location. There are two

options being considered by city council and the team. One would

put the Phillies "baseball only" stadium in Center City

Philadelphia. The other would put a stadium in South Philadelphia.

Almost as an afterthought, the local football team, would build

a new "football only" facility near the current dual

sport stadium just south of center city.

What this paper is about is the interactions between new sports

stadiums and their cities. What I will discuss is why stadiums

get built, how they are financed, those cities responses to the

challenges of getting them constructed, and the history and political

bickering that has enthralled Philadelphia in their most recent

stadium case. What does a new stadium do for a community?

History

Cities financing new stadiums isn't as recent a trend as one

would think. The first case of a city using municipal funds to

build a new stadium was Cleveland, Ohio in 1928. Cleveland Municipal

Stadium was finished in 1932, built in the beginning of the great

depression, it was part of the city's plan to attract the 1932

Summer Olympics (Gershman 142). It wasn't built with Cleveland's

baseball team in mind; they continued to play in League Park till

1946 (though they would play nights and weekends at Municipal

Stadium), and professional football wouldn't arrive till the late

thirties (in the form of the now St. Louis Rams) to Cleveland

as well. The first stadium built via public funds specifically

for a particular professional sport would be Milwaukee County

Stadium. Financing was approved and construction started in 1950

and was finished in 1953 in time for the Boston Braves baseball

team to become the Milwaukee Braves baseball team (Gershman 165).

At that time new stadiums, or updating or remodeling minor league

parks, were done more for getting a major league team for the

town's image, not as much for urban renewal. Though that would

change in the sixties.

Starting in the 1960s new stadiums served a double purpose. One,

to keep the teams "home" and not become someone else's

gold mine (Gershman 191);

and two as part of that community's urban renewal and economic

plan (Chema 20). In the case of the latter, the stadiums weren't

thought of as generating urban renewal, but as being part of the

greater scheme of urban renewal.

The idea was to take out two dilapidated areas (where the team

once played, and the area where the team would play) and replace

them with two new tax generating areas. In Cincinnati, the land

that was Crosley Field became an Industrial Park. In Pittsburgh,

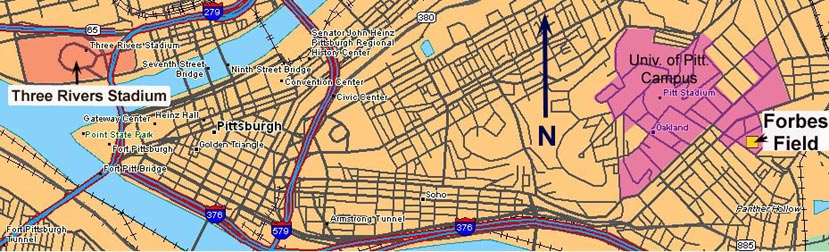

Forbes Field was torn down and the land was incorporated into

the University of Pittsburgh (see map below), while both cities

built new stadiums on their riverfront (Gershman 198).

The two Pittsburgh baseball park locations

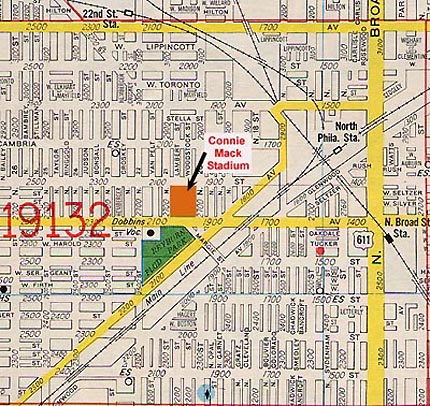

Though that's not always the case. After the 1970 season, The

Philadelphia Phillies started play in their new stadium, Veterans

Stadium, on the south side of town. The following year, Connie

Mack Stadium, the former home for the town's baseball team, on

the north side of Philadelphia, was damaged by fire. It stood,

as an eyesore for another five years till it was demolished in

1976 (Gershman 210). That plot of land stood unused for another

15 years till a church was built on its site in 1991 (Lowry 211).

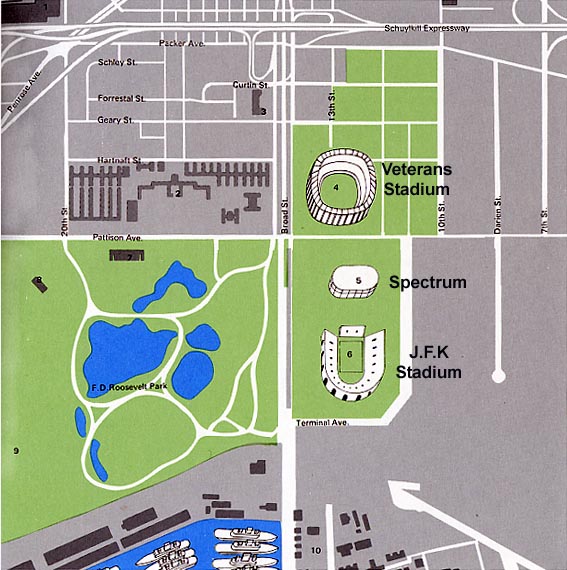

Veterans Stadium was incorporated into an area on South Broad

Street called the Sports Complex, so named for (then) having The

Spectrum for indoor sports, The Vet (as it's so called by the

locals) for outdoor sports, and JFK Stadium for other activities.

The only attraction for all being there? Easy access by car being

between two freeways due to its location.

Former Phils player Clay Dalrymple

walks the lot that was Connie Mack Stadium in 1989 (Photo by George

Tiedemann, Sports Illustrated)

The Deliverance Evengelical Church

stands where Connie Mack Stadium once stood (Photo taken by author

in 2001)

The Commodity

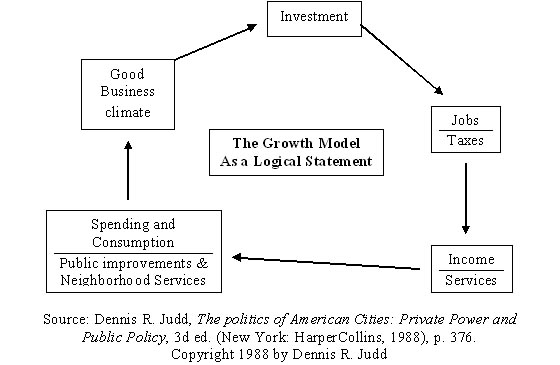

In the most recent round of stadium building, the idea of the

stadium as an investment has taken hold (Baade 2): the idea that

improved stadiums will create jobs, create a place to go to, and

start the urban renewal of an area. The proof however is quite

the opposite. What is the benefit to a local community if the

stadium contains all the amenities that a community would use

for it's economic well being? The owners of the sports franchise

get the receipts for the parking. They have food by way of their

vendors inside the stadium and having a bar and/or restaurant

built into the stadium as well. All the money in there goes to

the owner(s) of the  franchise (Cagan & deMause 147).

franchise (Cagan & deMause 147).

The community on the other hand gets nothing back in return Thev

get no money from public parking, for there are no public lots,

or already agreed to hand over the parking money to the team.

They can't even get money from parking tickets because there will

be an over abundance of parking lots so the customer won't have

the inconvenience of making sure they are parked legally. The

community's restaurants and bars get little or no traffic since

the fans will drive to one place, that being the stadium, instead

of making multiple stops. They will reside at the stadium's bar

or restaurant, being that it is conveniently located where they

are going to see the game (Cagan & deMause 141 ). The local

police department can't even get anything out of this arrangement.

If you crowd 20,000 cars into several parking lots, near to each

other, there will be no speeding. With all the lots, there will

be no illegal parking. All you have is traffic control as an expenditure

and nothing coming in as income. How can you have a win-win proposal

if the owners of the ball teams want every conceivable convenience

for their fans under their control?

When it comes to putting the new stadium in, there comes the sticky

situation of land assembly. The bigger the stadium, the more land

that is needed. If more land is needed, does one go to the suburbs

or beyond where fewer parcels are needed to be purchased and could

be less expensive to purchase? Do they instead stay in the city

and take their chances getting everything together sooner than

later. In actuality, only eight cities, currently and formerly,

had any of their sports teams playing in their suburbs (see chart

below). In seven of the cities, the football team played out in

the suburbs, in four of the cities the basketball team played

away from the city, in another three cities the baseball team

played away from the city. In one of the cases, the sport team

started out in the suburbs, then moved to the city, while the

former stadium was razed and the land eventually used as part

of a new mall (Lowry 181 ). This begs the question, why do most

of the teams (eighty four of ninety four professional teams) stay

within their home city's limits?

Chart of suburbs that host(ed) professional

sports teams

|

City |

Football |

Baseball |

Basketball |

|

Boston |

Foxburo |

|

|

|

Cleveland* |

|

|

Richfield |

|

Dallas |

Irving |

Arlington |

|

|

Detroit* |

Pontiac |

|

Auburn Hills |

|

Los Angeles* |

Anaheim |

Anaheim |

|

|

Minneapolis* |

Bloomington |

Bloomington |

|

|

New York City |

East Rutherford |

|

East Rutherford |

|

Washington D.C. |

Palmer Park |

|

Largo |

*- indicates that city doesn't have team(s) playing in

those suburbs anymore

The two possible conclusions for this would be the lack of

services the suburbs could provide (primarily water & sewer

and transportation) and residents of the suburb(s) not willing

to put up with the inconveniences of traffic, noise, and litter

caused by the inclusion of a new facility near them (Cox 29).

Any suburb lacking a freeway and an interchange from that freeway

would be at a disadvantage at attracting a sports stadium. The

city that controls the area's water and sewage will also dictate

where any new infrastructure would be built in the area as well.

With those factors against movement from the inner-city, the team

and its owners will look for the easiest way to do land assembly,

and over the course of recent sports history, governments have

helped the teams via eminent domain.

The inner city stadium: two scenarios

In urban renewal, the city will claim land by defining the needed

area, for the building, as being blighted and needing redevelopment.

Then eminent domain is

used by the government to obtain the land at a reduced rate than

what the market will give (Davis & Whinston 187). Then the

city can proceed with construction of the new structure and can

sell any extra land to developers to construct housing, or commercial

uses.

If only the stadium and nothing else is developed in the degenerated

section, then the investment by the city is lost. Customers will

go to the stadium and leave afterwards. There is nothing to keep

them around the neighborhood. Furthermore, if the stadium is the

only new structure built in the depressed area, then people going

to the stadium will think of their safety and travel by car so

as to avoid being in and around the area, before and after the

activity they attended. With that kind of structure, any other

sort of transportation (bus, subway, train, etc.) will never see

any attendance figured for it, because no one will want to risk

waiting or staying in a neighborhood one believes to be dangerous

(Gershman 234).On the other hand, you go through the first three

steps, mentioned before, but you have more land that can be redeveloped

than is needed by the city for the stadium. Then a neighborhood

can be created either by the government or developers. If the

creation of commercial, mixed use, or residential land is done,

then the investment by the city in the stadium can be paid off

via the other services the neighborhood provides citizens before

and after the activity they attend (Chema 20). Clean and walkable

streets, familiar emblems, and a comfortable environment will

encourage the "revitalization" of the area. Once the

neighborhood is established (or if by luck a new stadium intermeshes

with an existing neighborhood), the inclusion of mass transit

in there can further develop this sense of people feeling comfortable

being in the area. Therefore, they will leave their vehicles further

away or possibly not use them at all. though the buses, trains,

subways, or even trolleys must still run on time (having someone

stand in the rain because their connecting ride is fifteen minutes

late can hinder progress).

In the case of Philadelphia, before Veterans Stadium was completed,

the baseball and football teams played in different facilities.

Accessibility to either one was not easy. The baseball team played

at Connie Mack Stadium. It was in the middle of a working class

neighborhood. Access to the stadium by car was poor and parking

was lacking. The nearest train/subway station was five blocks

to the east of the stadium.

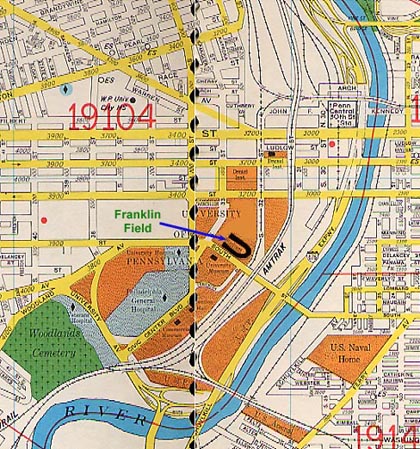

On the left, Connie Mack Stadium and the surounding

area. On the right, Franklin Field and the surounding area.

(Hagstrom map, 1980 copyright)

On the left, Connie Mack Stadium and the surounding

area. On the right, Franklin Field and the surounding area.

(Hagstrom map, 1980 copyright)

The football team played at Franklin Field on the grounds of

the University of Pennsylvania. Parking and access was average

(there is an exit with an interstate half a mile east of the stadium),

but not tremendous. The nearest train station was six blocks to

the northeast. but it was the Penn Central station for Philadelphia

so one could go anywhere on the east coast with ease from there.

With Veterans Stadium, you had an east-west freeway just to the

north of the stadium. You had a north-south freeway a mile and

a half south of the stadium (though the southern portion wouldn't

be completed till 1986). There was plenty of parking, due to the

combining of all the sports facilities in one area. The city also

extended the Broad Street subway line so there was a station next

to the stadium for those who couldn't or wouldn't use their cars.

It was not easy, all decisions made were political.

The original Philadelphia Sports

Complex, circa 1972

Bridging the Divide

Politicians like safe issues. Everyone is happy with the decision

and reelection is easy. Sports is an easy issue. Support the home

team. As a politician, however, support has other conotated meanings

to both the owners and the fans of the team.

For the owner, competition has its price in the way of salary

for the performers (meaning the players). To subsidize that price,

other income streams must be

found, and/or other costs must be reduced (Greenberg & Grey

136-138). Many of those solutions go through city hall or even

the statehouse. The owners will

plead poverty (as compared to the rest of the league) to the fans

in an attempt to get their help (Rosentraub, 1999).

To the fan, what is best for the team always comes out ahead.

The team needs good players to win championships. To get those

good players, however

the owners need money to pay the premium price for the best players

(Fizel, Gustafson, Hadley 83). The team can come out and say how

local officials are being unreasonable and they need more money

from the rent, the concessions, parking, or naming rights. The

fans will want the best for their team and interrogate the officials

who won't hand over the money for the team to do well. The good

of the city? Does it come by way of sport championships or quality

of life? The electorate can be fairly divided about that issue.

The points the electorate can split on are tax abatements and

subsidies. If the city builds the stadium, then they rent out

the space for those who want to use the space and the money from

that will repay the debt from construction (Greenberg & Grey

338). The sport team will want the rent as little as possible

so they have more money for other uses (Rosentraub 1999). If the

owner of the stadium (usually some bureaucratic body) reduces

the rent, then they will need to find other means to pay for the

stadium. It is there that a division point is created. If you

raise personal taxes, then the affected populace will not be happy.

Take money away from other services to cover the stadium, then

those who need those services will not be happy. If you have a

motel or taxi surcharge, then you'll see customers go elsewhere

or use other means in the metro area. You can have businesses

pay the difference, but your economy could be affected. Businesses

could move out or layoff workers. Mot a good situation for the

city in either case. There are many decisions that go into how

to finance a stadium. In the case of Philadelphia,

they are still going through many decisions that concern the current

and future stadiums there.

Philadelphia Time

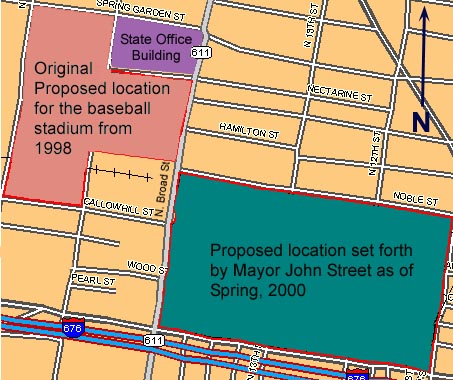

As mentioned on the first page of this paper, conversations

about replacing Veterans Stadium have been going on since 1994.

In the last three years, those conversations have become definite

plans. Coming to the new stadium game in the middle of this current

cycle of stadium building has provided Philadelphia the ability

to avoid some of the mistakes others before them had made. Already

news services reported back in February of 1999 that the state,

the city, and each sport team would divide the cost for the stadiums

between them equally, with each paying one third of the total.

The state and the sport teams have already put in their share,

it's the city of Philadelphia that is dragging its feet on the

money. There are two basic problems that are holding back Philadelphia's

part in this deal. The problems are where to build the baseball

stadium and how will the city finance their part of it. The original

idea was for the baseball only stadium to be on the north side

of downtown Philadelphia near the intersection of Broad and Spring

Garden Streets. It would been a fairly easy deal to pull off.

Only three properties to claim, one property belonged to the state,

anotherbelonged to the local newspaper publisher. It looked to

be fairly easy. However, one of the city council members was against

the plan because it affected his constituents negatively. Not

only the people living in the area, but those who worked at the

state office building didn't want to move or lose their jobs.

Then, some properties were sold in the area. That raised land

costs along which in turn raised the cost of the total project.

With the possibility of protest delaying indefinitely construction

and escalating land prices at their original site, then Mayor

Ed Rendell and the owners of the Phillies decided that the new

baseball stadium would instead be built near where the rest of

the stadiums and arenas are located, in South Philadelphia. The

plan would have the baseball stadium built to the northeast of

the current stadium (the Vet) on the stadium's north lot (Burton

& Yant 2-3). Still there were complaints and protests over

this site as well. Residents, who live to the west and north of

the South Philadelphia Sports Complex, brought out complaints

about what they have to endure currently with noise, litter, and

parking from the current facilities (Davies 8). They also had

a major ally on city council. Their city council representative

is the president over City Council. They might also have another

ally in the mayor. Back in April,2000, Mayor John Street came

forward with a proposal to build the new baseball only stadium

near the intersection of 12th and Vine Streets. It would be only

three blocks east of the original proposal for a baseball stadium.

John Street's proposal has several flaws to it. The first flaw

is in his proposal, is that there would be a hundred or more properties

to acquire in this plan as compared to the three properties at

Broad and Spring Garden or one at the stadium complex (Conlon

28). The second flaw is the time schedule. If the 12th and Vine

proposal is chosen, the new stadium won't be completed till 2005

at the earliest (Conlon 28). If the South Philadelphia were to

go through, it could be finished in 2003 (Benson 1 ) The last

flaw is the potential cost of building at 12th and Vine. Figures

for there are ranging from seven hundred million to one billion

dollars when all is said and done for that location. Estimates

for a new stadium in South Philadelphia have it around three hundred

fifty million dollars (Bostrom 4). With the state of Pennsylvania

already having eighty two million dollars (out of three hundred

fifty million for new stadiums in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh)

set aside for the building of a new baseball stadium in Philadelphia,

neither the team nor the state are interested in increasing their

cost in building a new stadium.

John Street's proposal has several flaws to it. The first flaw

is in his proposal, is that there would be a hundred or more properties

to acquire in this plan as compared to the three properties at

Broad and Spring Garden or one at the stadium complex (Conlon

28). The second flaw is the time schedule. If the 12th and Vine

proposal is chosen, the new stadium won't be completed till 2005

at the earliest (Conlon 28). If the South Philadelphia were to

go through, it could be finished in 2003 (Benson 1 ) The last

flaw is the potential cost of building at 12th and Vine. Figures

for there are ranging from seven hundred million to one billion

dollars when all is said and done for that location. Estimates

for a new stadium in South Philadelphia have it around three hundred

fifty million dollars (Bostrom 4). With the state of Pennsylvania

already having eighty two million dollars (out of three hundred

fifty million for new stadiums in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh)

set aside for the building of a new baseball stadium in Philadelphia,

neither the team nor the state are interested in increasing their

cost in building a new stadium.

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia Eagles football team has stayed in

the background during these proceedings. While everyone debates

where the baseball stadium should be, everyone involved has agreed

that the new football stadium should be built in South Philadelphia

(Hearsh 4). Designs for the stadium and its placement have already

been decided. The reason it hasn't been built is that the owners

of the football team have been unwilling to separate their part

in the city stadium funding deal from the baseball team. Why won't

the owners of the football team stand up and get a separate deal?

No one is certain, but the owners aren't familiar with Philadelphia

politics (they have only owned the team for four years and are

from Boston and Los Angeles respectively), and the team's recent

performance on the field has not inspired the city to help them.

As of the original writing, nothing had been settled concerning

when and where any stadiums will be built in Philadelphia.

Conclusion

Will it be worth Philadelphia's well being to build two new

stadiums for both of their sports teams? Seven hundred million

dollars for one stadium will outweigh any good that stadium can

produce directly or indirectly to a neighborhood. It would be

too much debt for any party involved to carry. However, it is

wise to spread the cost of building over as many different parties

as possible. It lowers the risk and doesn't hinder the governments

in funding other projects. Costs of stadiums will not go down.

As long as teams want stadiums more spread out and not towering

over the field, more land will be needed. As long as teams, and

governments, want stadiums constructed in urban areas, land prices

will be expensive. The combination of excesses in quantity of

land and cost of land will make government only investments in

subsidized infrastructures too exorberent to build.

The new round of stadiums effects on cities have yet to be fully

understood. Those who are against their subsidizing use prior

history to prove their point, but stadiums built between 1950

and 1985 were built with a different purpose than those built

since 1985. Inner-city stadiums must have a multitude of non-stadium

options nearby if they are to spur economic development. Those

who advocate building stadiums mention the name recognition the

city gets from television showing pictures of the city during

game broadcasts as one of the indirect positives. The payday for

the city, if they would build one of these modem stadiums, would

come by attracting big time events to the city by the new stadium.

If your new stadium has all the required amenities, you can have

the Super Bowl or one of the sport's all-star games played in

your city. The sports teams, though, needs its patrons to spend

their money on their grounds. Neither side can satisfied their

own economic outcome without the other side being hurt.

For Philadelphia, considering all the options, the new stadium

plan left behind by Mayor Rendell should be the one completed.

It has both the baseball and football teams getting separate facilities

in South Philadelphia. The best site for a new stadium might be

along the Delaware River between the Walt Whitman and Ben Franklin

bridges. However no one is considering any sites along there.

Of the sites that are under consideration, building near the current

stadium is the best option. The cost for all is the lowest there,

and all the sites north of the interstate won't spur the economic

growth the politicians would like to see. It would be an disadvantage

to the city to have the stadiums away from the rest the city's

attractions. South Philadelphia isn't near any attractions, but

the lower cost in building there compared to North Broad wins

out. Both teams stay, and the teams, the politicians, and the

fans of both teams will be happy.

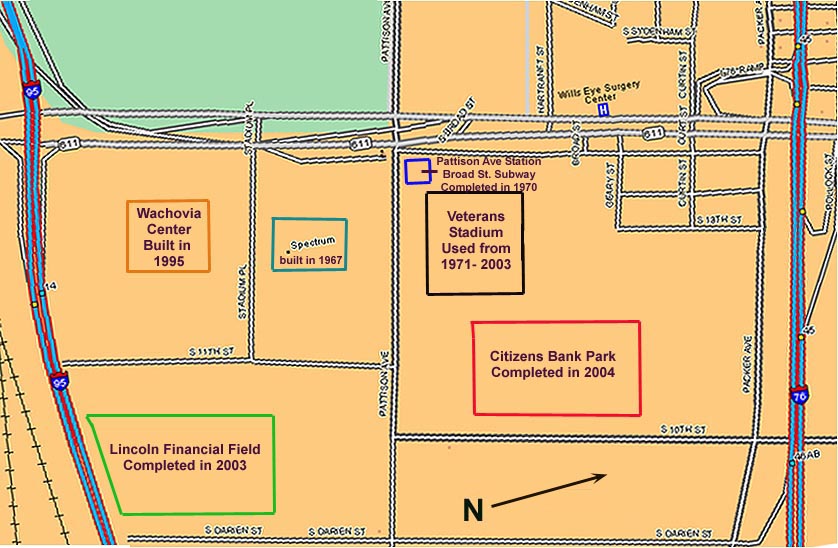

Postscript - I've drawn in on this map below the aproximate

locations of the current sports arenas in the Philadelphia Sports

Complex along with the location of the now demolished (as of March

28, 2004) Veterans Stadium as well.

This paper was originally written, back in May, 2000 for the

Urban Political Geography course I took at Ohio State University,

taught by Prof. Kevin Cox.

I found this paper in

January, 2003 and got around to placing it on roadfan.com on April

14, 2004.

Questions and comments about the subject matter here can be

directed to roadfan@copper.net

Return to the Philadelphia Virtural Roadtrip

or the Igglephans link page