Why

I-73 Has Not Been Built in Ohio Yet

Introduction

Transportation

is geography, but transportation can be political as well. You

have land use issues, development concerns, and problems of political

chain of command. These problems are evident when concerning the

building of interstate freeways. You have federal officials mandating

its building, state officials scrambling to find funding for it,

and local leaders debating whether or not to go along with this

idea. Limited access, divided highways are one way to alleviate

traffic problems, but no one wants that solution near them. These

people's defense will include that their farmland is the best,

their woods are the most scenic, or that they had moved from the

"city" and did not want to go back to it. These circumstances

helped to shape the debate about Interstate 73 in Delaware County,

Ohio

Transportation

is geography, but transportation can be political as well. You

have land use issues, development concerns, and problems of political

chain of command. These problems are evident when concerning the

building of interstate freeways. You have federal officials mandating

its building, state officials scrambling to find funding for it,

and local leaders debating whether or not to go along with this

idea. Limited access, divided highways are one way to alleviate

traffic problems, but no one wants that solution near them. These

people's defense will include that their farmland is the best,

their woods are the most scenic, or that they had moved from the

"city" and did not want to go back to it. These circumstances

helped to shape the debate about Interstate 73 in Delaware County,

Ohio

I want to show 4 points in this paper. How I-73 came about and

it's history in Central Ohio. How the process for choosing a routing

for I-73 proceeded and doomed it to failure. Why the public never

was entirely behind the I-73 project. Finally, how funding for

the project was blundered away by one state government department

that has delayed the construction for now. Between 1991 and 1996,

plans were organized for an interstate freeway to go north-south

through Ohio. Those plans have yet to be put into action, in Ohio,

due to two factors; the state has never been able to get favorable

public opinion to back it; and the lack of funds in the state

of Ohio to build it. The focus of most of the discussion about

this freeway concerns the routing of I-73 in Delaware County,

Ohio. It is there that the need for a new freeway is greatest,

but the protest against it was the strongest as well. Why has

Interstate 73 yet to be built in Ohio?

History

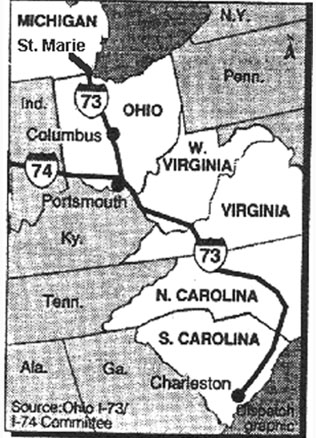

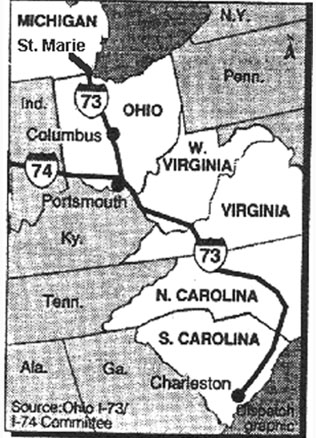

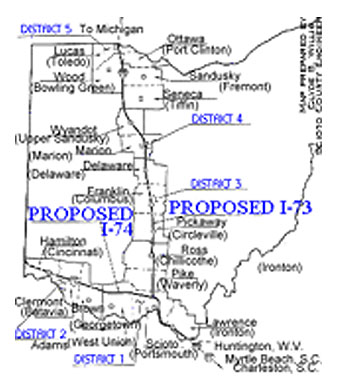

Interstate 73 was first proposed in 1991 as part of The Intermodal

Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA). ISTEA would

have created a "National Highway System." This would

be a United States Congress established system of highways of

national significance, as compared to the original system of freeways

established with section 7 of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944

. One of the routes designated in the 1991 bill was a Great Lakes

to Mid Atlantic Corridor. It would connect Detroit, Toledo, Columbus,

Huntington, Bluefield, Winston-Salem, and Charleston South Carolina.

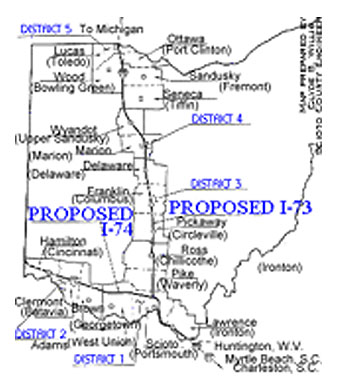

This routing was given the numeral designation I-73. For the Ohio

portion, I-73 was to follow US 23 from Toledo to Portsmouth and

US 52 from Portsmouth to Chesapeake where it would go into West

Virginia. The routing of I-73 seemed fairly easy to do everywhere

in the state of Ohio, except in Delaware, Franklin, and Pickaway

Counties. In that area lay one of  the major difficulties in getting I-73 from paper to

concrete and asphalt.

the major difficulties in getting I-73 from paper to

concrete and asphalt.

In a case of lucky foreshadowing, in 1990 (then) Governor George

Voinovich had approved expanding the Ohio Turnpike Commission's

authority to allow it to fund other highway projects, other than

the current Ohio Turnpike. This gave Ohio a "backdoor"

approach for highway funding if the Ohio Department of Transportation

(ODOT) did not have enough funds to properly plan or construct

any new highways. By the end of 1993 Governor Voinovich had given

approval for the Ohio Turnpike Commission (OTC) to do a feasibility

study for the proposed I-73 in Ohio. For the next three years

I-73 would be an OTC project with ODOT having no part in planning

it. This would ultimately affect the future of the project.

Two years after the US Congress had designated it for construction,

I-73 first came to light for much of the public in late 1993 with

the announcement that the OTC would do a feasibility study of

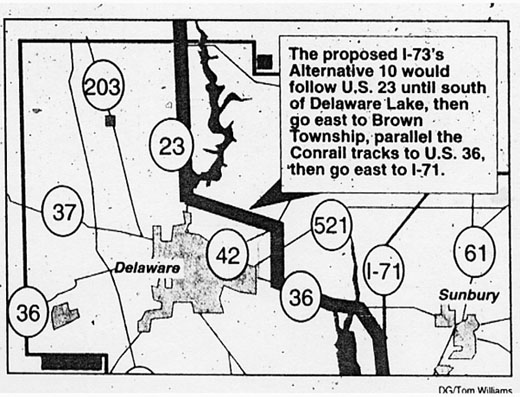

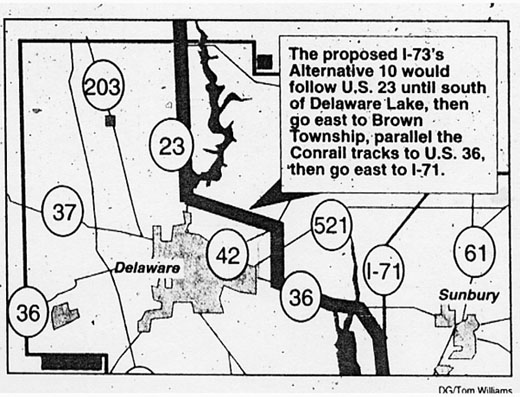

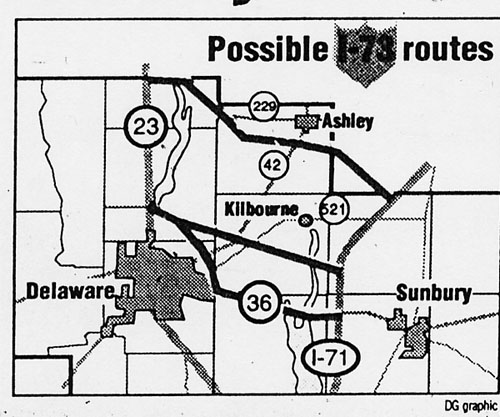

it. The preliminary idea for routing I-73 in Delaware County was

to have it go south along US 23, from Marion County, to between

the south end of Delaware Reservoir and the north end of Delaware

city limits. From there I-73 would branch off to the east then

south going around NE Delaware to US 36 east. I-73 would go along

US 36 east to I-71, where it would leave US 36 and multiplex with

I-71 into Columbus. The state of Ohio did have a committee that

worked on the routing of the I-73 corridor. They did however also

asked for a local preference as to where I-73 should be built.

At that time though, no one had done any traffic routing studies

for the freeway. So due to a lack of empirical backing to help

select a route the answer from the local Delaware committee at

that time was essentially, 'We don't know. Give us some numbers

to help us choose.'

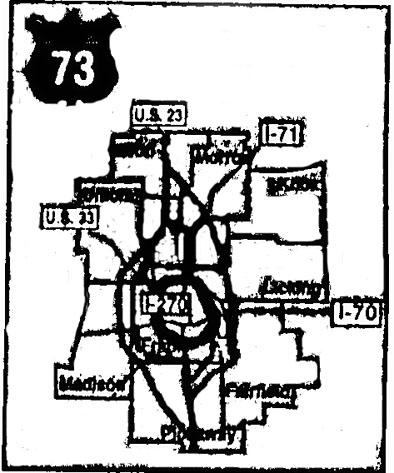

Over the course of six months between progress reports, development

plans in the northeast section of Columbus were quickly beginning

to interfere with the  proposals.

With the advent of the Polaris Amphitheater and the (then) new

Bank One headquarters in Southern Delaware County and development

starting on Leslie Wexner's Easton, the added traffic that I-73

would bring to the freeways of that area was a concern for local

planners. Various people and organizations brought forth debate,

alternatives, and suggestions as to the routing and necessity

of I-73. One idea was the proposed building of another outerbelt

around Columbus. There were also proposed routes going directly

south from Delaware to I-270 using US 23 or SR 315, or going southwest

along US 42, from Delaware, to US 33 then back to I-270 in Dublin.

Still, none of these suggestions were under any sort of official

consideration or study yet (thus no maps were made of these ideas).

proposals.

With the advent of the Polaris Amphitheater and the (then) new

Bank One headquarters in Southern Delaware County and development

starting on Leslie Wexner's Easton, the added traffic that I-73

would bring to the freeways of that area was a concern for local

planners. Various people and organizations brought forth debate,

alternatives, and suggestions as to the routing and necessity

of I-73. One idea was the proposed building of another outerbelt

around Columbus. There were also proposed routes going directly

south from Delaware to I-270 using US 23 or SR 315, or going southwest

along US 42, from Delaware, to US 33 then back to I-270 in Dublin.

Still, none of these suggestions were under any sort of official

consideration or study yet (thus no maps were made of these ideas).

In spite of a lack of actual studies, in 1994 the first stated

estimates for I-73, from the Ohio Turnpike Commission, were two

billion dollars if it was all built from scratch, with possibly

several hundred million being deducted if I-73 could overlap existing

limited access highways. Allan Johnson, of the OTC, also came

out with a time frame for construction of the freeway. He said

a decision to build or scrap the project would come in late 1995

or early 1996. The design work would take another two years, and

construction would start in 1997. The OTC even went as far as

to say that the Delaware section would be built first with Johnson

saying, "...I think that could provide some of the most beneficial

things soonest." However, Delaware officials stated that

they were having difficulty in contacting members of the OTC and

were becoming impatient over this lack of communication.

Several months later, attitudes improved with the knowledge that

a feasibility study was underway and would be completed in March

of 1995. With that study, an official cost and alignment for I-73

would be known as well . It was soon after this that the first

letter to the editor of the Delaware paper concerning I-73 was

published. In it was a theme that would be heard many times over

the following two years. There were no good routes. Any route

would force people and businesses to relocate, thus creating more

problems than solutions, and not to mention encouraging the population

boom in Delaware County.

Process Begins

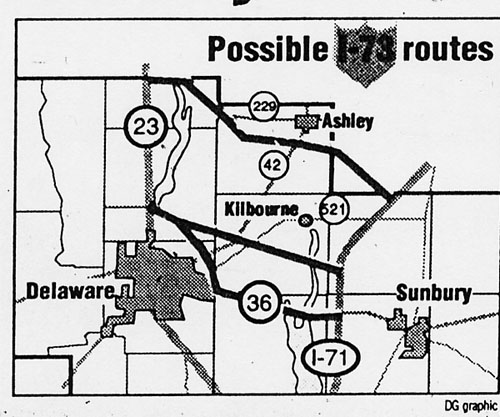

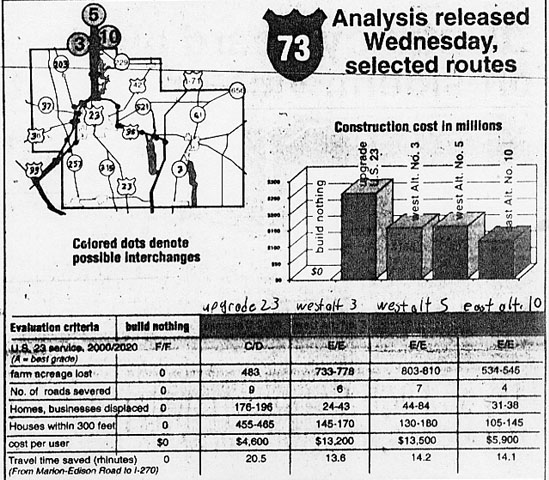

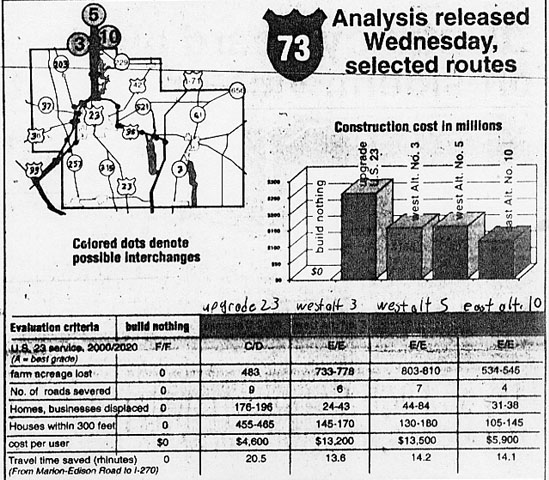

On March 16, 1995, the I-73 debate began in earnest. That was

the date on which the first proposed corridors for I-73 in and

around Columbus were publicly announced. Eight different alternatives

for routing I-73 though Delaware county were mapped out, and included

were several more involving the surrounding  counties. Cost estimates for the route

between Circleville and Marion, which would go through Delaware

County, ranged from two hundred sixty-one million dollars to six

hundred seventy-seven million dollars, pending on I-73's routing

and how much of the current road system would be used.

counties. Cost estimates for the route

between Circleville and Marion, which would go through Delaware

County, ranged from two hundred sixty-one million dollars to six

hundred seventy-seven million dollars, pending on I-73's routing

and how much of the current road system would be used.

When the local officials looked at the plans, they were skeptical

that I-73 would help to alleviate any transportation problems.

Their main concern was lightening the traffic load on US 23, south

of Delaware. None of them felt that any route that branched off

from US 23, north of Delaware, would help with their traffic problems.

If they could get I-73 to go around south and west of Delaware

however, it could ease traffic access to the industrial park in

the SW portion and help diffuse traffic concerns on the NW side

as well. However, the routing of I-73 to the west of Delaware

would affect an avigational easement needed for expansion of the

local airport's main runway to five thousand feet. It could also

have possibly taken out a city park in the northwest end of Delaware

as well . When one local resident asked about regulations protecting

environmental features making I-73 feasible or even thinkable,

an OTC member responded, "If it isn't, we're going to have

gridlock, a parking lot between Delaware and Columbus. Wetlands

can be "mitigated," but it's expensive... I hope we

don't bankrupt the country with regulations like that." The

question became how does a state official, based in Cleveland,

know more about local traffic than the Delaware county and city

officials do. Showing all this "concern" without any

studies done showed I-73 as a top-down project being forced upon

the citizenry.

Public Reaction

The citizenry came out in force. To say the least, the general

public's view was extremely negative. Regularly, any public meeting

concerning I-73 in Delaware had the most attendees in that series

of meetings. Surprisingly, despite the public view, OTC members

were constantly stating publicly that they were pleased with the

large turnouts in Delaware. However, the OTC's single minded focus

was fairly evident in one statement after the first public showing

of the I-73 plans. James Brennan, of the OTC, theorized that most

visitors were "positive" about the I-73 proposal, and

many would like construction to start immediately. Maybe yes,

maybe no. Stated comments from the public at large contrasted

with that view. "We fought really hard to keep the dam out

... and now we're going to have to fight the highway." "We

did not build out there to be two miles from the highway. 71 is

close enough. We moved out here to be in the country."

So the sides were drawn. State officials wanted the I-73 corridor,

but were never forthcoming in releasing informational details

to the local officials. Local officials were divided over this

project. Some saw it as possibly helping Delaware's transportation

concerns, others saw it as someone else's idea being forced down

their throat and that it wouldn't help the county, or the city.

Delaware officials viewed I-73 rather oddly. They always talked

about it in a local sense, never expanding their boundaries past

the state borders, or mentioning that it was federally mandated

to be built as part of a bigger system. The public's reaction

was unsure. They saw the need for it, but no one wanted the route

running near their area.

The first group to come out against a routing of I-73 were residents

in Brown Township in Delaware County in April of 1995. This group

was mostly farmers who did not want to give up their land. They

saw a routing of I-73 through their area as causing them in particular

more problems than it would solve. They did not want to sacrifice

farm land, homes, and local businesses that would cause "economic

detriment to township residents." Their first meeting, where

their opposition was formed, drew thirty-five people. Their second

meeting drew over a hundred people. Their tactics were to get

county officials to support their protests, search for other groups

against I-73, and continue to write letters to politicians who

could influence the project.

How the OTC Bowed Out

Meanwhile, at this same time, the OTC decided to increase the

tolls on the Ohio Turnpike eighty percent. Their reasoning was

to help pay for widening the turnpike to three lanes in each direction

the entire length of the turnpike and for replacement of all sixteen

service plazas along the turnpike. There was no mentioning of

new highways or I-73 specifically when they did this. The toll

hike raised eyebrows and suspicions among state politicians and

others however.

The OTC got into a bad habit of giving out varying estimates on

their projects. They borrowed twenty-four million to pay for three

new interchanges in 1994, and those interchanges showed up again

the following year being funded by the proposed toll hike. Over

the course of the summer of '95, the OTC had published estimates

on the cost of expanding the turnpike rise seventeen percent.

When asked where the money from the year before went, Turnpike

Executive Director Allen Johnson said, "It's been used for

other projects," but Johnson could not say specifically where

the money went. "I can't (tell you) right off the top of

my head. We have so many projects under way," he told the

Cleveland Plain Dealer. The financial records of the OTC at that

time showed that they had $106.7 million dollars on hand and more

in investments that could cover much of the costs of the current

turnpike expansion, without having to raise tolls.

This was a red flag to the state's Congressional Transportation

Committees. The Ohio House produced a bill that would limit the

OTC to only a ten percent increase in its tolls by July 1st of

that year, and all other increases would have to be brought in

front of public hearings and the legislature would have a committee

to oversee the OTC. One state representative tried to block the

use of OTC funds for I-73, but his proposal was negated. State

Senator Scott Oelslager soon after then brought out a proposal

that would end the OTC's involvement with I-73, and any other

highway project that wasn't connected to the current Ohio Turnpike.

His bill would have let the OTC finish it's study of I-73 (everyone

agreed that there was no sense in stopping mid-stream, and forcing

someone else to start over sometime in the future), then it would

be out. Oelslager's stated reasoning was to limit authority of

the governor on transportation needs by keeping the OTC out of

ODOT's work (a complete opposite of Voinovich's intentions when

he authorized the OTC's involvement in the I-73 project). By January

of 1996, the Ohio Turnpike Commission conceded to these pressures

and decide to bow out of the I-73 project, after the study was

completed. Possible construction was to be declared an Ohio Department

of Transportation future project. However ODOT had no funding

for construction of the freeway for the appreciable future, so

there was no sensible time frame.

Final Decision

Meanwhile,

the local I-73 committee worked on choosing a proposed route.

With the protests coming largely from the eastern half of Delaware

County, officials looked to the western half for a solution for

I-73 . Citizens there caught on quickly and protested the highway

going through their area. Due to that, the committee crossed off

the western routes and looked at a central and southern route.

Again, people protested the freeway coming through their neighborhood.

That sent the committee back to the original plan for I-73. The

original plan would have I-73 go along US 23 to near Delaware,

then bypass the city to the North and east to US 36, then go east

to I-71 to go south to Columbus. It would cost the least to build

for ODOT. It would take up the least amount of farmland, housing,

businesses, and it would affect the fewest number of roads. This

routing would do the least harm for everyone involved.

Meanwhile,

the local I-73 committee worked on choosing a proposed route.

With the protests coming largely from the eastern half of Delaware

County, officials looked to the western half for a solution for

I-73 . Citizens there caught on quickly and protested the highway

going through their area. Due to that, the committee crossed off

the western routes and looked at a central and southern route.

Again, people protested the freeway coming through their neighborhood.

That sent the committee back to the original plan for I-73. The

original plan would have I-73 go along US 23 to near Delaware,

then bypass the city to the North and east to US 36, then go east

to I-71 to go south to Columbus. It would cost the least to build

for ODOT. It would take up the least amount of farmland, housing,

businesses, and it would affect the fewest number of roads. This

routing would do the least harm for everyone involved.

Interestingly it wasn't the most direct or the quickest route,

and traffic study results were mixed. There were arguments for

all the traffic to stay on US 23, but that would lead to massive

congestion that no highway(s) could cure on the approach to I-270.

Some even went as so far as to state that the bypass would be

so problematic to traffic in southern Delaware County, that it

wasn't even worth being built. Some believed the bypass in itself

would create more traffic and become a congested future issue.

Finally, there remained the rest who thought the bypass would

be just fine.

On April 24, 1996 after much consternation and teeth gnashing

the Northeast Delaware by-pass option was accepted as the routing

of I-73 through Delaware County. Delaware City officials and others

from outside Delaware County supported the plan. However in opposition

to the city, county officials did not care for the final routing,

citing that it was no solution to any of the current problems

with traffic in Southern Delaware County. Further more, the public

was up in arms, denouncing the decision. Interestingly, all became

quiet the issue not long after.

With I-73 falling under the auspices of ODOT, lack of funding

has kept the building of this highway quiet for four years now,

and for who knows how much longer. Even a member of ODOT came

out and, proclaimed that the latest status of Interstate 73, at

least in reference to the proposed linking of U.S. 23 with Interstate

71 across central Delaware County is, "dead. I don't know

how else to say it ... Those are political realities ... Basically,

people said they didn't want it."

Conclusion

Where did the various proposals for I-73 go wrong? The Ohio

Turnpike Commission mishandled public and political communication

and thus funding for construction of I-73 was indefinitely postponed.

The inability of OTC and other local planners to have a proposal

that could solve some of Delaware's transportation problems in

an economic fashion caused local officials to disagree on the

freeway. The city of Delaware backed the I-73 plan. Delaware County

officials held their opinion till the end, but eventually came

out against I-73. Their indecision went parallel with the mood

of Delaware County citizens, who were opposed to any proposed

route that would affect them personally, but were supportive as

long as it was someone else's backyard. An analogy for the citizens

would be that they were not able to see the forest for the trees.

These people only cared about themselves and for the present.

It is that kind of thinking that doomed I-73. Eventually I-73

will be built through Ohio and Delaware County, just that the

problems described here have only postponed the inevitable from

happening.

Sources

Untill I can figure out how to add footnotes along the way,

the sources for this paper are as follows: Frank Gerlach-I-73/74

corridor webpage, 1997. Richard Weingroff. Delaware Gazette. Toledo

Blade. Allen Johnson (OTC director in 1994). Unknown OTC member

at a Delaware meeting. Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Ray

Lorello.

This paper was originally written in the Spring of 2000 for

Urban Political Geography (Geog 660) taught by Kevin

Cox at Ohio State University. This paper was slightly

revised in March, 2001 for the American

Association of Geographers National Conference.

Originally

linked to Roadfan.com on October 1, 2001/ Remade on August 6,

2003

Questions and comments concerning this paper can be sent to

Sandor Gulyas

Return to the I-73 in Ohio page.

Transportation

is geography, but transportation can be political as well. You

have land use issues, development concerns, and problems of political

chain of command. These problems are evident when concerning the

building of interstate freeways. You have federal officials mandating

its building, state officials scrambling to find funding for it,

and local leaders debating whether or not to go along with this

idea. Limited access, divided highways are one way to alleviate

traffic problems, but no one wants that solution near them. These

people's defense will include that their farmland is the best,

their woods are the most scenic, or that they had moved from the

"city" and did not want to go back to it. These circumstances

helped to shape the debate about Interstate 73 in Delaware County,

Ohio

Transportation

is geography, but transportation can be political as well. You

have land use issues, development concerns, and problems of political

chain of command. These problems are evident when concerning the

building of interstate freeways. You have federal officials mandating

its building, state officials scrambling to find funding for it,

and local leaders debating whether or not to go along with this

idea. Limited access, divided highways are one way to alleviate

traffic problems, but no one wants that solution near them. These

people's defense will include that their farmland is the best,

their woods are the most scenic, or that they had moved from the

"city" and did not want to go back to it. These circumstances

helped to shape the debate about Interstate 73 in Delaware County,

Ohio the major difficulties in getting I-73 from paper to

concrete and asphalt.

the major difficulties in getting I-73 from paper to

concrete and asphalt. proposals.

With the advent of the Polaris Amphitheater and the (then) new

Bank One headquarters in Southern Delaware County and development

starting on Leslie Wexner's Easton, the added traffic that I-73

would bring to the freeways of that area was a concern for local

planners. Various people and organizations brought forth debate,

alternatives, and suggestions as to the routing and necessity

of I-73. One idea was the proposed building of another outerbelt

around Columbus. There were also proposed routes going directly

south from Delaware to I-270 using US 23 or SR 315, or going southwest

along US 42, from Delaware, to US 33 then back to I-270 in Dublin.

Still, none of these suggestions were under any sort of official

consideration or study yet (thus no maps were made of these ideas).

proposals.

With the advent of the Polaris Amphitheater and the (then) new

Bank One headquarters in Southern Delaware County and development

starting on Leslie Wexner's Easton, the added traffic that I-73

would bring to the freeways of that area was a concern for local

planners. Various people and organizations brought forth debate,

alternatives, and suggestions as to the routing and necessity

of I-73. One idea was the proposed building of another outerbelt

around Columbus. There were also proposed routes going directly

south from Delaware to I-270 using US 23 or SR 315, or going southwest

along US 42, from Delaware, to US 33 then back to I-270 in Dublin.

Still, none of these suggestions were under any sort of official

consideration or study yet (thus no maps were made of these ideas). counties. Cost estimates for the route

between Circleville and Marion, which would go through Delaware

County, ranged from two hundred sixty-one million dollars to six

hundred seventy-seven million dollars, pending on I-73's routing

and how much of the current road system would be used.

counties. Cost estimates for the route

between Circleville and Marion, which would go through Delaware

County, ranged from two hundred sixty-one million dollars to six

hundred seventy-seven million dollars, pending on I-73's routing

and how much of the current road system would be used.  Meanwhile,

the local I-73 committee worked on choosing a proposed route.

With the protests coming largely from the eastern half of Delaware

County, officials looked to the western half for a solution for

I-73 . Citizens there caught on quickly and protested the highway

going through their area. Due to that, the committee crossed off

the western routes and looked at a central and southern route.

Again, people protested the freeway coming through their neighborhood.

That sent the committee back to the original plan for I-73. The

original plan would have I-73 go along US 23 to near Delaware,

then bypass the city to the North and east to US 36, then go east

to I-71 to go south to Columbus. It would cost the least to build

for ODOT. It would take up the least amount of farmland, housing,

businesses, and it would affect the fewest number of roads. This

routing would do the least harm for everyone involved.

Meanwhile,

the local I-73 committee worked on choosing a proposed route.

With the protests coming largely from the eastern half of Delaware

County, officials looked to the western half for a solution for

I-73 . Citizens there caught on quickly and protested the highway

going through their area. Due to that, the committee crossed off

the western routes and looked at a central and southern route.

Again, people protested the freeway coming through their neighborhood.

That sent the committee back to the original plan for I-73. The

original plan would have I-73 go along US 23 to near Delaware,

then bypass the city to the North and east to US 36, then go east

to I-71 to go south to Columbus. It would cost the least to build

for ODOT. It would take up the least amount of farmland, housing,

businesses, and it would affect the fewest number of roads. This

routing would do the least harm for everyone involved.